As a

follow-up to my post from last week titled “Whose Interpretation of Huawei

v. ZTE Will Prevail in 2025?”, I thought it might be useful to compare

three different interpretations of that decision. One is the UPC Munich Division’s interpretation

as reflected in last month’s decision in in Huawei v. Netgear, which (I

think it is fair to say) is consistent with what has been the dominant interpretation

by the German judicial system so far.

Another is the approach advocated by the European Commission in its

amicus brief in HMD Global v. VoiceAge.

A third is the approach the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom

articulated in its 2020 decision in Unwired Planet Int’l Ltd. v. Huawei

Techs. (UK) Co. Ltd., [2020] UKSC 37.

All three of these authorities are reading the same paragraphs of the

same decision, and yet they come to rather different conclusions about what it

all means.

First,

here are some excerpts from Huawei v. ZTE that are cited by the other

three authorities. (In deciding what to

excerpt, of course, I’ve had to exercise some

judgment, without simply quoting everything.)

46 It is . . . settled case-law that the

exercise of an exclusive right linked to an intellectual-property right — in

the case in the main proceedings, namely the right to bring an action for

infringement — forms part of the rights of the proprietor of an intellectual-property

right, with the result that the exercise of such a right, even if it is the act

of an undertaking holding a dominant position, cannot in itself constitute an

abuse of a dominant position . . . .

47 However, it is also settled case-law that

the exercise of an exclusive right linked to an intellectual-property right by

the proprietor may, in exceptional circumstances, involve abusive conduct for

the purposes of Article 102 TFEU . . . .

48 Nevertheless, it must be pointed out . .

. that the particular circumstances of the case in the main proceedings

distinguish that case from the cases which gave rise to the case-law cited in

paragraphs 46 and 47 of the present judgment.

49 It is characterised, first . . . , by the

fact that the patent at issue is essential to a standard established by a

standardisation body, rendering its use indispensable to all competitors which

envisage manufacturing products that comply with the standard to which it is

linked.

50 That feature distinguishes SEPs from

patents that are not essential to a standard and which normally allow third

parties to manufacture competing products without recourse to the patent

concerned and without compromising the essential functions of the product in

question.

51 Secondly, . . . the patent at issue

obtained SEP status only in return for the proprietor’s irrevocable

undertaking, given to the standardisation body in question, that it is prepared

to grant licences on FRAND terms.

52 Although the proprietor of the essential

patent at issue has the right to bring an action for a prohibitory injunction

or for the recall of products, the fact that that patent has obtained SEP

status means that its proprietor can prevent products manufactured by

competitors from appearing or remaining on the market and, thereby, reserve to

itself the manufacture of the products in question.

53 In those circumstances, and having regard

to the fact that an undertaking to grant licences on FRAND terms creates

legitimate expectations on the part of third parties that the proprietor of the

SEP will in fact grant licences on such terms, a refusal by the proprietor of

the SEP to grant a licence on those terms may, in principle, constitute an

abuse within the meaning of Article 102 TFEU.

54 It follows that, having regard to the

legitimate expectations created, the abusive nature of such a refusal may, in

principle, be raised in defence to actions for a prohibitory injunction or for

the recall of products. However, under Article 102 TFEU, the proprietor of the

patent is obliged only to grant a licence on FRAND terms. In the case in the

main proceedings, the parties are not in agreement as to what is required by

FRAND terms in the circumstances of that case.

55 In such a situation, in order to prevent

an action for a prohibitory injunction or for the recall of products from being

regarded as abusive, the proprietor of an SEP must comply with conditions which

seek to ensure a fair balance between the interests concerned.

56

In this

connection, due account must be taken of the specific legal and factual

circumstances in the case (see, to that effect, judgment in Post Danmark,

C‑209/10, EU:C:2012:172, paragraph 26 and the case-law cited). . . .

60 Accordingly,

the proprietor of an SEP which considers that that SEP is the subject of an

infringement cannot, without infringing Article 102 TFEU, bring an action for a

prohibitory injunction or for the recall of products against the alleged

infringer without notice or prior consultation with the alleged infringer, even

if the SEP has already been used by the alleged infringer.

61 Prior to such proceedings, it is thus for

the proprietor of the SEP in question, first, to alert the alleged infringer of

the infringement complained about by designating that SEP and specifying the

way in which it has been infringed. . . .

63 Secondly, after the alleged infringer has

expressed its willingness to conclude a licensing agreement on FRAND terms, it

is for the proprietor of the SEP to present to that alleged infringer a

specific, written offer for a licence on FRAND terms, in accordance with the

undertaking given to the standardisation body, specifying, in particular, the

amount of the royalty and the way in which that royalty is to be calculated. .

. .

65 . . . [I]t is for the alleged infringer

diligently to respond to that offer, in accordance with recognised commercial

practices in the field and in good faith, a point which must be established on

the basis of objective factors and which implies, in particular, that there are

no delaying tactics.

66 Should the alleged infringer not accept

the offer made to it, it may rely on the abusive nature of an action for a

prohibitory injunction or for the recall of products only if it has submitted

to the proprietor of the SEP in question, promptly and in writing, a specific

counter-offer that corresponds to FRAND terms.

67 Furthermore, where the alleged infringer

is using the teachings of the SEP before a licensing agreement has been

concluded, it is for that alleged infringer, from the point at which its

counter-offer is rejected, to provide appropriate security . . . . The

calculation of that security must include, inter alia, the number of the past

acts of use of the SEP, and the alleged infringer must be able to render an

account in respect of those acts of use.

68 In addition, where no agreement is

reached on the details of the FRAND terms following the counter-offer by the

alleged infringer, the parties may, by common agreement, request that the

amount of the royalty be determined by an independent third party, by decision

without delay.

69 Lastly . . . an alleged infringer cannot

be criticised either for challenging, in parallel to the negotiations relating

to the grant of licences, the validity of those patents and/or the essential

nature of those patents to the standard in which they are included and/or their

actual use, or for reserving the right to do so in the future. . . .

71

It follows from all the foregoing considerations that . . . Article 102 TFEU

must be interpreted as meaning that the proprietor of an SEP, which has given

an irrevocable undertaking to a standardisation body to grant a licence to

third parties on FRAND terms, does not abuse its dominant position, within the

meaning of Article 102 TFEU, by bringing an action for infringement seeking an

injunction prohibiting the infringement of its patent or seeking the recall of

products for the manufacture of which that patent has been used, as long as:

– prior to bringing that action, the

proprietor has, first, alerted the alleged infringer of the infringement

complained about by designating that patent and specifying the way in which it

has been infringed, and, secondly, after the alleged infringer has expressed

its willingness to conclude a licensing agreement on FRAND terms, presented to

that infringer a specific, written offer for a licence on such terms,

specifying, in particular, the royalty and the way in which it is to be

calculated, and

– where the alleged infringer continues

to use the patent in question, the alleged infringer has not diligently

responded to that offer, in accordance with recognised commercial practices in

the field and in good faith, this being a matter which must be established on

the basis of objective factors and which implies, in particular, that there are

no delaying tactics.

Second,

here is a translation of some excerpts from the EC’s amicus brief interpreting

some of the above paragraphs:

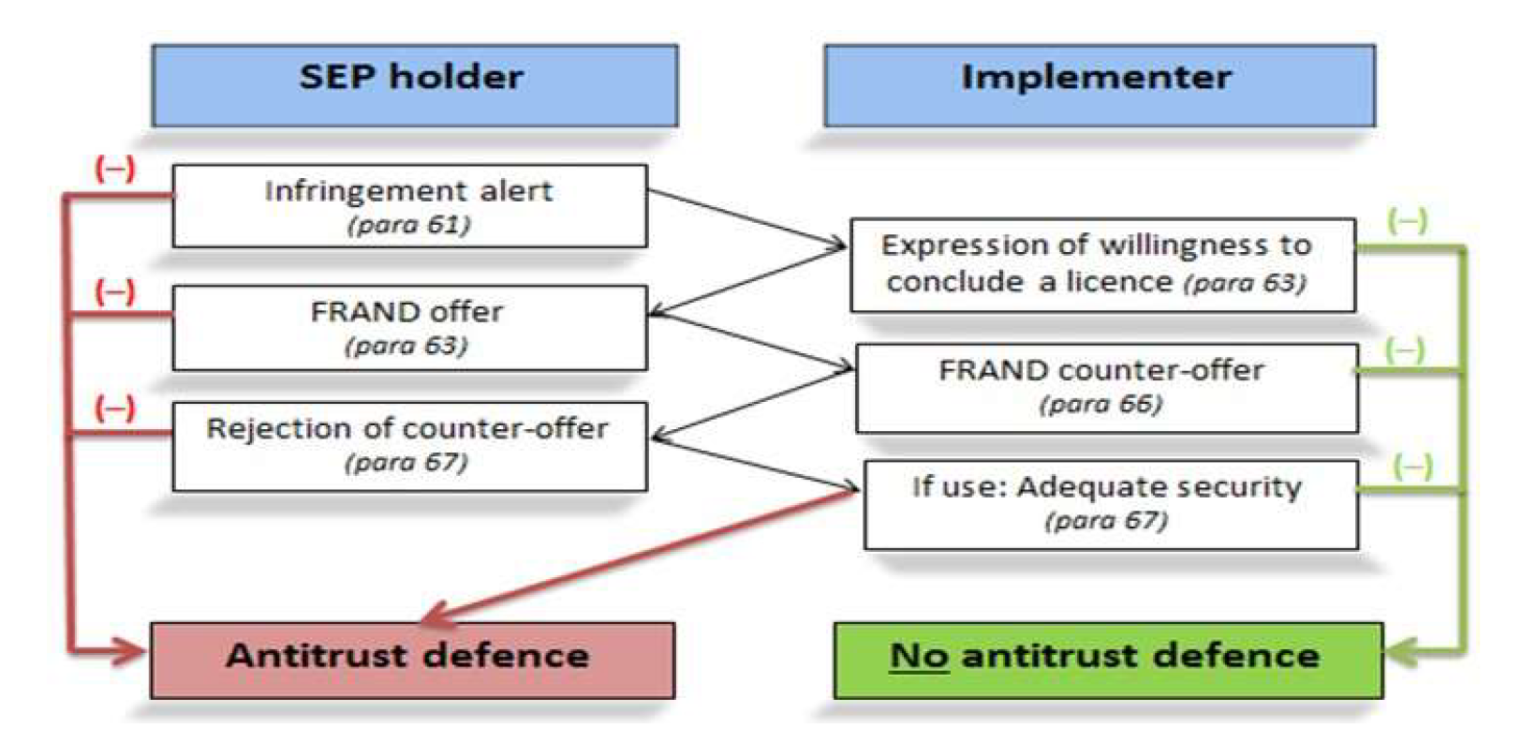

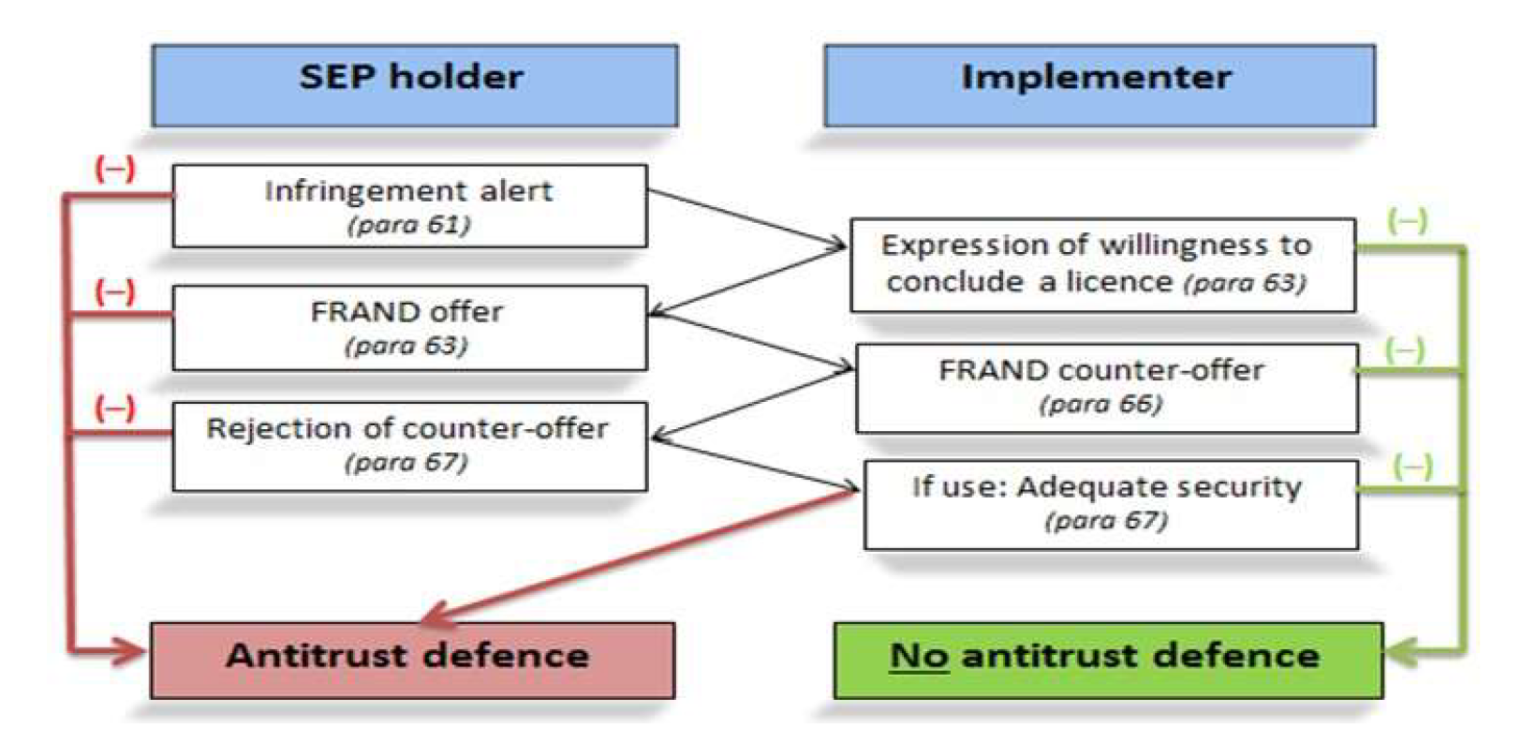

55 The procedural steps defined by

the Court of Justice of the European Union in the Huawei judgment can be

illustrated graphically as follows:

64 As follows from the wording of

the Huawei judgment, the Court of Justice of the European Union first

requires the SEP holder to send a notice of infringement to the alleged patent

user, which (i) expressly complains of patent infringement, (ii) names the

patents concerned with their number and (iii) specifies the manner of

infringement in the letter itself. . . .

66 The European Commission is also of

the opinion that the Huawei framework requires that the notice of

infringement be served before an action for an injunction is brought. . . .

71 The European Commission is further

of the opinion that the various steps of the Huawei framework must be

examined in their respective sequence. Only if the first step has been properly

completed can the second step be examined. The same applies to all subsequent

steps. Mixing is not permissible, however, because the balance between the

various interests [footnoting here to Huawei v. ZTE para. 55] . . . sought

by the Court of Justice of the European Union in the Huawei judgment otherwise

would not be guaranteed.

72 The purpose of the Huawei

framework is to create an environment in which the SEP holder and the patent

user can enter into a license on FRAND terms without the pressure of an

injunction. The SEP holder may request an injunction only if the patent user

has previously had the opportunity to conclude a license on FRAND terms. On the

other hand, the user of an SEP who does not have a license must express its

willingness to conclude a license on FRAND terms and end the situation of

unauthorized use of the SEP. The Huawei framework strikes a balance

between the interests of the SEP holder and the patent user and must be

strictly adhered to in order to maintain this balance. . . .

87 Therefore, in the European

Commission's view, mixing steps 2 and 4 would compromise the balance of

interests sought by the various Huawei steps and their precise

sequencing. In particular, such an approach would allow the court to grant an

injunction without having to examine whether the SEP holder has submitted a

license offer on FRAND terms. However, this would contradict the Huawei judgment.

Third,

here is a translation of some of the salient portions of the UPC Munich Division’s

decision in Huawei v. Netgear (beginning at p.128):

According to the decision of the

European Court of Justice, the SEP holder, to whom the SEP confers a dominant

market position, must first inform the patent user of the patent infringement

of which he is accused as a first step before bringing an action for injunctive

relief. In doing so, he must identify the SEP in question and state how it is

alleged to have been infringed (ECJ para. 61). It had already become

established in the cited case law of national courts that the sending of claim

charts is sufficient for these purposes in any case . . . . Insofar as the

European Commission takes the view in its opinion in this context that this

reference must be made in the letter itself (amicus curiae letter para. 65),

such a formalistic understanding cannot be accepted. To be sure, a reference to

a general website of the SEP holder, which does not contain any easily

accessible information on the specific patent in suit, may too little to be

regarded as sufficient notice. For good reason, however, the judgment of the CEJU

does not establish any strict formal requirements, but leaves it up to the

courts of the Member States to assess each individual case. . . .

The Mannheim Local Division [in Panasonic

v. OPPO] and the European Commission agree that the initial declaration of

willingness to license is the prelude to further negotiations. It must not be

limited to mere lip service, but must be serious, as described by the Federal

Court of Justice [in Sisvel v. Haier]. However, consideration of the

respective declaration alone does not generally lead to a determination of

whether the implementer is seriously interested in taking a license. . . . For

this purpose, the respective behavior must always be considered in an overall

view . . . .

The Mannheim Local Division agrees

to the extent that it states . . . that the further conduct of both parties

during the subsequent negotiations should not be excluded from consideration

during the subsequent examination of the FRAND defense. Rather, both the SEP

holder and the infringer must behave “in accordance with commercial practice”

during the negotiations and work in good faith towards the conclusion of a

license agreement. Their conduct must therefore be assessed according to

whether it sufficiently takes into account the fundamental objective of the CJEU’s

negotiation program, to achieve through targeted negotiations a timely

conclusion of a FRAND license agreement primarily on a private-autonomous basis. This requirement results in obligations to be

specified for the individual case at each stage of the negotiations. Whether a

(counter)offer meets FRAND criteria cannot be determined independently, but can

only be assessed on the basis of the specific negotiations and the behavior of

the parties. . . .

This [paragraphs 65-67 of Huawei

v. ZTE] means that the user may invoke the infringement of antitrust law in

the context of a defense against that part of the action which is aimed at

injunction, recall or destruction, but only if he himself has submitted a

concrete counteroffer without delaying tactics, which corresponds to FRAND

conditions and, in the event of its rejection, has provided appropriate

security and information about the scope of the acts of use.

The background to this is that,

according to the CJEU, the FRAND objection under antitrust law is not primarily

concerned with how a FRAND license fee is to be calculated; rather, it is a question

of whether the patent proprietor has abused its dominant position by bringing a

patent infringement action for an injunction against the infringement of its

patent or for the recall/destruction of the products for the manufacture of

which that patent was used, without the following two conditions being met [quoting

Huawei v. ZTE para. 71] . . . .

The court deduces from paras. 65-67

and 71 above that even if the patentee's offer is not FRAND and the user

nevertheless makes a counteroffer, he must provide security and submit

assignments. . . .

Furthermore, before the examination

of the FRAND-conformity of the patent owner’s offer, it is regular to consider

whether the implementer has fulfilled the requisite conditions for the

infringement court to engage in this examination. To the Commission and the Mannheim Local

Division it is to be admitted, that under such an understanding the possibility

exists, that the infringement court's examination of the offer of the

competition-law-bound SEP owner remains completely undone or only cursorily

carried out (compare Mannheim Local Division, Decision of 11.22.2024,

UPC-CFI-210/2023, paras. 195-98). This

is correct. But this outcome corresponds

to the decision of the CJEU in paras. 66 and 67 [of Huawei v. ZTE]. Conversely, the infringer remains free to

enforce its claim for the granting of a license on FRAND conditions, be it

grounded in competition or contract law, within the framework of its own claim

in an appropriate (competition law) court.

In the UPC, the possibility remains in place for the infringer also to

assert a counterclaim for the granting of a license (compare Mannheim Local

Division, Decision of 11.22.2024, UPC-CFI-210/2023, paras. 236-41).

Fourth,

here are some excerpts from the UKSC’s decision from 2020:

129. Huawei argues that the CJEU

there [in Huawei v. ZTE] laid down a series of mandatory conditions

which must be complied with if a SEP owner is to obtain injunctive relief. If

the SEP owner fails to comply, its claim for an injunction will be regarded as

an abuse of its dominant position, contrary to article 102 TFEU. In the Court

of Appeal, Huawei’s argument was that the SEP owner had to have complied before

even issuing proceedings for injunctive relief . . . . It is not entirely clear

whether Huawei continues to pursue its argument in quite such absolute terms.

Although our attention is invited to other respects in which Unwired failed to

comply with the CJEU’s conditions, Huawei’s central focus now is upon Unwired

not having made a FRAND offer at any stage, its offers being too high to be

FRAND. It is not enough, Huawei says, for a SEP owner to be willing to enter

into a licence agreement on terms determined by the court; it has to make a FRAND

licence offer itself. In Huawei’s submission, Birss J therefore erred in granting

Unwired an injunction when it had not complied with the CJEU’s conditions. It

should have been limited to damages.

130. Unwired responds that Birss J

and the Court of Appeal interpreted Huawei v ZTE correctly, and it

presented no obstacle to the grant of an injunction. Unwired accepts the

conclusion of the lower courts that the CJEU did lay down one mandatory

condition, namely the notice/consultation requirement in para 60, which must be

observed by the SEP owner, who will otherwise fall foul of article 102. But, in

its submission, that is the sole mandatory condition that the CJEU laid down;

the other steps set out by the court were intended only as a “safe harbour”. If

they are followed, the SEP owner can commence proceedings for injunctive relief

without that amounting to an abuse of its dominant position, but failure to

follow them does not necessarily mean that article 102 is infringed, because it

all depends on the circumstances of the particular case. . . .

149. In our view, Birss J and the

Court of Appeal interpreted the CJEU’s decision in Huawei v ZTE

correctly.

150. Bringing “an action for a

prohibitory injunction … without notice or prior consultation with the alleged

infringer” will amount to an infringement of article 102, as para 60 of the

CJEU’s judgment sets out. In that paragraph, the language used is absolute: the

SEP owner “cannot” bring the action without infringing the article.

151. We agree with Birss J and the

Court of Appeal, however, that the nature of the notice/consultation that is

required must depend upon the circumstances of the case. That is built into the

reference to “notice or prior consultation”, which conveys the message that

there must be communication to alert the alleged infringer to the claim that

there is an infringement, but does not prescribe precisely the form that the communication

should take. This is to be expected, given that the CJEU had just introduced

its discussion of the conditions which seek to ensure a fair balance between

the various interests concerned in a SEP case with a very clear statement, at

para 56 (set out above), that account had to be taken of the specific legal and

factual circumstances in the case. In so saying, the court was reflecting its

well-established approach in determining whether a dominant undertaking has

abused its dominant position, as it demonstrated by its reference back to the Post

Danmark case, and the case law there cited. It also makes obvious sense

that the court should have built in a degree of flexibility, given the wide

variety of factual situations in which the issue might arise, and the fact that

different legal systems will provide very different procedural contexts for the

SEP owner’s injunction application. In Germany, for example, as we observed

earlier, validity and infringement are tried separately, so that the alleged

infringer faces the risk that the SEP owner could obtain a final injunction

against it without validity first being determined, and in some member states,

an injunction might be granted before a FRAND rate is determined. In contrast,

in the United Kingdom, it is not the practice to grant a final injunction

unless the court is satisfied that the patent is valid and infringed, and it has

determined a FRAND rate.

152. The court’s statement in para

56 also colours the interpretation of the scheme it set out between paras 63

and 69 of its judgment. As the Court of Appeal observed, para 56 does not sit

comfortably with the notion that the CJEU was laying down a set of prescriptive

rules, intending that failure to comply precisely with any of them would

necessarily, and in all circumstances, render the commencement of proceedings

for an injunction abusive. It is important, it seems to us, to take account of

where para 56 is placed in the judgment. Immediately preceding it, the court

had identified the very real problem that occurs where, as in the case which

had generated

the reference to it, there is no agreement as to what terms would be FRAND, and

then said (in para 55, quoted above) that “in order to prevent” an action being

regarded as abusive, the SEP owner must comply with “conditions which seek to

ensure a fair balance between the interests concerned”. This identifies what

the conditions need to seek to ensure, but is no more prescriptive than that,

and it is of considerable significance that para 56 immediately follows,

requiring that “[i]n this connection”, which must surely be a reference back to

the conditions which seek to ensure a fair balance, due account must be taken

of the specific legal and factual circumstances of the case. It would be

surprising if the steps then set out by the CJEU were expected by it to apply

in all cases, no matter what their legal and factual circumstances.

153. Unwired submits that the

language used by the CJEU is language intended to signpost a safe harbour for

the SEP owner. We agree that this does lend a degree of support to Unwired’s

argument. In particular, in contrast to the absolute language of para 60, in

para 71, the court speaks of the SEP owner not abusing its dominant position

“as long as” it follows the steps laid out. This does not tell us that if the

SEP owner does not follow the steps, it will be abusing its dominant position.

To answer that, due account has to be taken of the particular circumstances of

the case, although, of course, it is likely to be valuable to compare what

occurred with the pattern set out by the CJEU. . . .

(Note,

by the way, that according to this

article by Tom Brazier and Andrew Sharples, “Under section 6 of the European

Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, Huawei v ZTE constitutes ‘retained EU case

law’ that could bind UK Courts. Initially, this retained EU case law could only

be departed from by the Supreme Court. However, this was modified under section

6 of the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Act 2023 to allow ‘a relevant

appeal court’ to depart from any retained EU case law, ‘except so far as there

is relevant domestic case law which modifies or applies the retained EU case

law and is binding on the relevant appeal court’. To date, however, the Supreme

Court's ruling in Unwired Planet v Huawei has not been reconsidered and,

as such, the Supreme Court’s judgment remains valid.”)

What

I find most interesting about all of this is that both the UPC and the UKSC believe

that CJEU’s decision in Huawei v. ZTE should be read flexibly, and that

the overrall facts and circumstances need to be taken into account in

determining whether there has been an abuse of dominant position; but they draw

different conclusions about how that flexibility is to be taken into

account. The UPC’s underlying premise,

in my view, is consistent with the German judiciary’s approach that the

overarching goal is to nudge the parties into deciding for themselves what a FRAND

royalty is (see the reference above to “the fundamental objective of the CJEU’s

negotiation program, to achieve through targeted negotiations a timely

conclusion of a FRAND license agreement primarily on a private-autonomous basis”). By contrast, I would say that the U.K.’s

approach is consistent with the proposition that, as long as the SEP owner

provides adequate notice, and the parties eventually agree to abide the terms

of a court-determined FRAND license (even at the last minute, see here),

that is sufficient to remove the abuse of dominant position question from consideration;

but it will then be the court, not the parties, who establish the terms of the

FRAND license. (See also my discussion here

about differences between the two jurisdictions, in the context of the Panasonic

v. OPPO decision.) The EC’s position

as expressed in the amicus brief is more formalistic than either of these, which might also be a defensible position, depending on one's point of view; and

it clearly sees the CJEU’s decision as establishing something more in the nature of a

strict test, though like the U.K. approach it would require the courts to establish

the terms of FRAND licenses in some cases, which is something we have yet to

see from the UPC or the German courts.